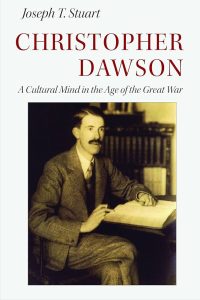

Stuart, Joseph T. Christopher Dawson: A Cultural Mind in the Age of the Great War. Catholic University of America Press: Washington, D.C., 2022. 454 pp.

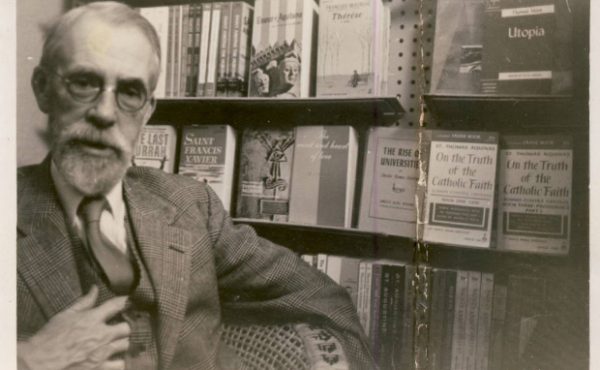

2022 saw the publication of the masterful biographical study of the British cultural historian Christopher Dawson (1989 – 1970), by Joseph T. Stuart. CUA Press is at the vanguard of a burgeoning renaissance of interest in the life and work of Christopher Dawson, having published critical editions of his major works under the editorship of the late Don Briel (1947 – 2018), and with a forthcoming release of a new edition of a biography written by his daughter, Christina Scott.

While some great publications detailing Dawson’s life and his work already exist, Stuart’s contribution is unique, providing a biographical study that contextualizes Dawson and his intellectual and cultural vision against the backdrop of the implosion and fragmentation of European culture that began with the First World War and which continued, according to Stuart, at least until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991. Stuart demonstrates a wide reading not only of Dawson’s own work, but the work which Dawson himself engaged in. He presents what he refers to as Dawson’s “cultural mind” in all the breadth and depth that it was, as he brought together a multiplicity of various disciplines of his time such as anthropology, ethnography, archaeology, history, and sociology — some of which were very new — to get past various reductive modes of rendering reality and to “see things whole” (6).

As Stuart describes it, “The purpose of this book is to excavate the frame of Dawson’s cultural mind in order to demonstrate how it not only reconciles intellectualist and behaviorist approaches to culture but also provides a synthesis helpful in thinking about the relationship between religion and politics, reforming education as enculturation, coordinating specialized research, and constructing a more meaningful cultural history today” (6–7). And in the opinion of this reviewer, Stuart is largely successful in fulfilling the book’s stated purpose by means of his dexterous mastery of Dawson’s sizable published corpus, and also through an impressive command of the significant archival resources made available at a number of Dawson archives, both in England and in the Unites States, not to mention his familiarity with Dawson’s own source material, as well as the most contemporary of history of the period covering Dawson’s life.

As Stuart describes it, “The purpose of this book is to excavate the frame of Dawson’s cultural mind in order to demonstrate how it not only reconciles intellectualist and behaviorist approaches to culture but also provides a synthesis helpful in thinking about the relationship between religion and politics, reforming education as enculturation, coordinating specialized research, and constructing a more meaningful cultural history today” (6–7). And in the opinion of this reviewer, Stuart is largely successful in fulfilling the book’s stated purpose by means of his dexterous mastery of Dawson’s sizable published corpus, and also through an impressive command of the significant archival resources made available at a number of Dawson archives, both in England and in the Unites States, not to mention his familiarity with Dawson’s own source material, as well as the most contemporary of history of the period covering Dawson’s life.

The book proceeds in two parts, the first of which covers off on the development of Dawson’s cultural mind, examining how Dawson brought together the various disciplines he did in order to create a rigorous “science of culture.” As Stuart describes it, “culture is so complex that no single formal object sufficiently makes it intelligible” (11), all of which meant that Dawson had to incorporate a variety of (sometimes new) disciplines, to get at the understanding go culture that he so earnestly desired, and desired to communicate. The author presents Dawson’s unique dexterity across a multiplicity of disciplines, but is careful to show how Dawson’s approach did not fall into the kind of superficiality which seems to plague much of what passes for interdisciplinary work nowadays. Instead, Stuart depicts Dawson as a truly transdisciplinary thinker, what he refers to as Dawson’s “cultural mind.” It is in part one where we find Dawson’s explorations of the very idea of culture, along with chapters on Dawson’s engagement with and use of the disciplines of sociology, history, and comparative religion.

Part two examines the application of Dawson’s cultural mind in the areas of politics and education specifically. One gets a real sense of how valuable Dawson’s cultural mind is in its application to the many problems that plagued Europe and the West following the Great War and throughout the twentieth century. One cannot help but see how valuable the intellectual framework that he developed, and out of which he operated, would be if it were able to be employed today in the face of the past few years’ worth of global pandemic, war in Europe, and what seems like almost universal unrest. The sheer breadth and openness of Dawson’s cultural mind is one which deserves both study in and of itself as well as emulation in our own cultural milieu.

While the focus of this work is squarely on Dawson’s cultural mind, the expansive nature of that mind is such that no aspect of culture seems to have been left out — the work also doubles as something of its own cultural history of English-speaking Europe between the wars. Stuart has demonstrated that he is precisely the right person to take us on this journey of discovery, exhibiting his own remarkable aptitude for following Dawson’s lead in finding the balance between prescriptive and descriptive approaches to culture, allowing the truth of things to reveal itself instead of getting caught up in telling his own story. While he is obviously an admirer of Dawson, Stuart is unafraid to critique his work where appropriate, demonstrating that he himself (Stuart, that is) has developed something of a cultural mind of his own. Stuart has done a tremendous service to us all bringing this book to publication, one can hope for a wide readership not only for specialists, but to the educated generalist who is eager to develop a cultural mind of their own and who is open to exploring non-reductive approaches to our current cultural conundrums.

While not everyone will agree with everything that Dawson wrote or thought, none can dismiss him as a reactionary or a thoughtless ideologue. It seems that we all have something to learn from Dawson, and one could do no better than to take this volume as either an introduction to the man and his thought, or an opportunity to think through again what Dawson has made available through his cultural mind.

* this review was first published at Homiletic and Pastoral Review