The present is built upon the stories we tell of the past. Thus folklore, myth, legends, and history, are concerned at least as much with who we are today as with what our ancestors might have got up to. This is true not just of individuals, but of whole societies and nations.

Australia has its own stories it tells about itself. A lucky country. A modern, diverse, and progressive nation. A land built upon equality. A ‘fair go’. Each of these identities are founded on a story or stories we tell about our past.

Of course, there are contesting stories as well. Australia was settled. Or it was invaded. It owes its success to its Western patrimony. Or it is still fighting to rectify the sins of this past. Australia is a monarchy tied to its British heritage. Or it is a temporarily frustrated Republic looking toward the ‘future’. It is a nation built upon the ‘free market’. Or it is a society where governments support the most vulnerable.

Our understandings of the past are often negotiated through ideological concerns and these have only a passing regard for what actually happened. Thus mythology (which is necessary for any ideology, but is out of favour in a post-Enlightenment world) is reintroduced to the public sphere disguised in the garments of historical truth.[i]

Museums are one medium by which the past is mediated into the present. In my own state, Western Australia, the WA Museum Boola Bardip which opened in 2020 is the premier example. Among its permanent exhibitions are galleries dedicated to the story of Western Australians.

The museum’s exhibits range from leisure and recreation to everyday living to the experience of overseas conflict and war. Through the galleries, the stories of our ancestors are crafted. Ordinary people faced with hardship in a strange land. People who were hard-working with practical intelligence. People who loved to play and watch sport. People not so different from you or me.

But stories are crafted as much from the elements that are left out as those that are put in. And through this lens, we can see another aspect to the story that it being told. And that is that Australia is a secular, or ‘post-religious’ nation. For among the exhibits telling the story of Western Australians are few indirect and no direct (at least as far as I could see) references to faith, belief, or religion.

*****

Australia does not have the same markers of religious faith or spirituality as some other countries. We are lacking in roadside shrines, have no holy wells, and few sites of pilgrimage. The landscape is of course sacred in various ways to the Aboriginal people, but this is a spirituality that requires inculcation to recognise these markers of spirituality or faith.

What Australia does have however is its churches.

A church, usually either of the Anglican or Catholic persuasion, seems to have been one of the first public buildings constructed by early European settlers. These churches might be accompanied by other civic constructions, in most cases an agricultural hall. Here either the church or hall might double as a school room, dance hall or other host of civic functions. Where the church was constructed in the early-mid 19th century, it is also likely to be surrounded by a local cemetery.

In larger towns other buildings including gaols, police stations, courts, hotels, and pubs all became markers of public life. But in the smaller, more rural settings, it seems that it was mostly the church and (sometimes) the agricultural hall that was required.

As travel became easier and faster, first through the train lines and later through the internal combustion engine, these small rural churches and halls gradually fell into disuse. Often, it seems, the agricultural hall was dismantled and its materials used elsewhere. In my own rural locality, the original hall can still be seen 15 kilometres south of its original positioning serving today as the headquarters of the Toodyay branch of the Country Women’s Association.

Yet, in many places, the churches still stand. Some, it is true, have been sold and converted to private use. But others still function as sites of religious worship and reminders of the concerns and priorities of past generations of Australians.

The purpose of this series of posts then is to document some of these churches and the place they might hold in the Australian story (or at least in the story of the localities to which they are attached). I am hoping that this will give me a structure to springboard into other ideas or stories that might attach themselves to these buildings.

The series will be non-denominational, and I aim to prioritise those buildings that have been left behind as civil and public society has gravitated towards the towns or cities.[ii]

If you know of such a church, I would appreciate any recommendations that come my way.

*****

St Philip’s Church at Culham

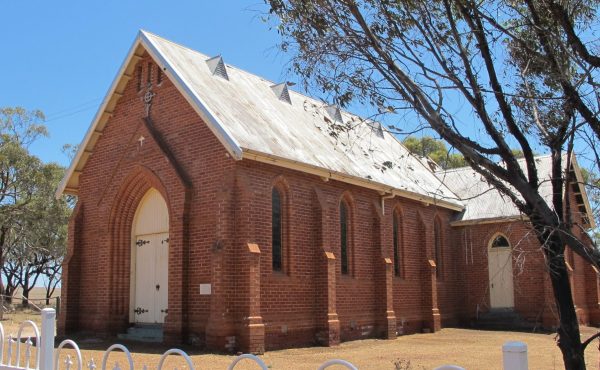

Buildings don’t come much older in Western Australia than St Philip’s Anglican Church at Culham. Construction began in 1850 (21 years after the founding of the Swan River colony) though construction was delayed, and the church opened in 1857. By ecclesiastical quirk however, the building was not formally consecrated until 1895.

The church is closely linked to it benefactor, Samuel Pole Phillips, born in Oxfordshire, England, who in 1839 at 20 years of age arrived in the Swan River Colony and took up land in the Toodyay valley. Phillips was, by all accounts, a man whose personality was larger-than-life. Physically speaking, he was an imposing man, standing more than six-foot (in the 19th century no less) and, in his later life, sporting a beard to the centre of his chest.

Philips was a man of custom and tradition. He went by the title ‘Squire’ and wished to import a British landed gentry to Australia insisting, where he was able, that the norms and manners of his adopted country mirrored those of England. There are accounts of Philips in his old age being driven to his neighbours (who he insisted were his tenants) where the older folk would humour him by tugging their forelocks as a traditional sign of respect.

Yet Philips was obviously also a brave and energetic man. In 1865, when in South Australia, Phillips was issued a medal for bravery when he rode his horse into rough surf and saved the lives of two men thrown from a boat (he was unable to save a further four men who drowned in the same incident). He lived for some sixty years in the colony and he, and several of his nine children, are buried in the cemetery of St Philips at Culham.

An overall simple construction, St Philip’s at Culham is a brick and stone build in a gothic style. As is typical of older buildings resting upon clay foundations, the building has shifted over time and today one side of the building is stabilised with iron rods.

Yet the clear jewel in the crown of St Philips is the single stained-glass window on the northern end of the church. There is no electricity and few windows in the church and its simple interior does not distract from the light shining through the window.

As of writing, services are held on the fifth Sunday of the month (whenever that occurs) however in December the church opens for carols the week before Christmas. These are truly carols by candlelight[iii] (no electricity remember). The gathered congregation are an eclectic mix of local farmers, descendants of the inhabitants of the cemetery, and a healthy mix of families local to the area, mine own included.

I’ll admit that the music would win no prizes, though it is capably supported by a couple of musicians who play a variety of instruments. Moreover, taking children to evening carols (or indeed evening anything) can also be running the gambit especially as it approaches a toddler’s dinner time. For the second half of last year’s carols therefore, I found myself outside the church on a wooden bench while two of my boys ran about with a couple of other children, threading their way between graves.

It was dusk. The sky above was just losing its last vestiges of colour. Insects and bats were ducking and diving in the air above the valley. The sound of singing issued softly from the church while the glow of candles streamed faintly from the open door.

I can’t be sure how ‘Squire’ Samuel Pole Phillips might have liked the scene. One suspects that the services he attended at St Philip’s, Culham featured a little more decorum, certainly more than my sons were demonstrating at any rate. But though it is said of Philips that he had a quick temper, it has also been recorded that this was offset by his fondness for children.

I, at least, choose to believe that Philips would be heartened by the scene, some 160 years after the church he donated was opened and some 120 years after Philips himself left this world for a better. Eighty-two years and nine children are not a bad innings. And I understand that his descendants still farm in the valley. Yet, for all of that, I would not count the small church in Culham the least of his legacy.

[i] This is an essay for another time.

[ii] Though I could be tempted by a particularly significant church within a town or city.

[iii] Battery powered candles. December in the Wheatbelt is not the time to mess with an open flame.