The following is an entry in the “Church’s of the Wheatbelt” series. An introduction to the series can be read here.

November is traditionally the month of honouring the dead. This custom comes from Europe and the Mediterranean. Its symbolism of pumpkins, haybales, and falling leaves harkens strongly to these origins. It is little wonder that November, with its shortening of days, the gathering of crops, and the coming of frosts, stands as a reminder to those who live in northern latitudes of the mutability and the mortality of all things.

In my own southern climate, there is some disconnect with this memento mori. Indeed, November is a month where days grow longer (and warmer) and one’s mind begins to turn towards barbeques and the beach. Yet parallels between these northern and southern Novembers do exist, at least for those who are willing to exercise just a little imagination.

The European winter is a season of dormancy. Yet in my climate, with its hot, dry summers and wet winters, it is not winter so much as summer that is the season when nature rests. And even as plants and grasses set seed and die in the autumn of the northern hemisphere, roughly the same time, though here in late spring, do the plants and grasses around my own home set seed and die.

Other parallels might also be observed. For those in the northern hemisphere the onset of winter, with its snow and ice, meant a seasonal increase in mortality. But for much of Australian history (that is until the early 20th century) one was more likely to die in the Australian summer. Mortality has shifted in favour of winter in more recent decades, as deaths attributed to infectious and parasitic declined, yet for much of Australia’s history, December, January, and February were the deadliest months of the year.

November too is the month in which Remembrance Day falls when most Australians with pause at the eleventh hour to remember those soldiers killed in the First World War. Thus, and in spite of its longer, warmer days, November can be thought of as a very appropriate time for remembrance of those who have died and a reminder that we too must join them.

And this, brings me to the Church of St Saviour’s in Katrine.

Halfway between the towns of Toodyay and Northam, lies a causeway across the Avon River. Converted from a natural ford in the 1860s, the location of this safe passage across the river naturally formed the focus of a settlement during the early history of European colonialisation. In this period Katrine was a developed town complete with post office, inn, school, and store. But of this settlement all that remains today is Katrine Homestead and the Church of St Saviour.

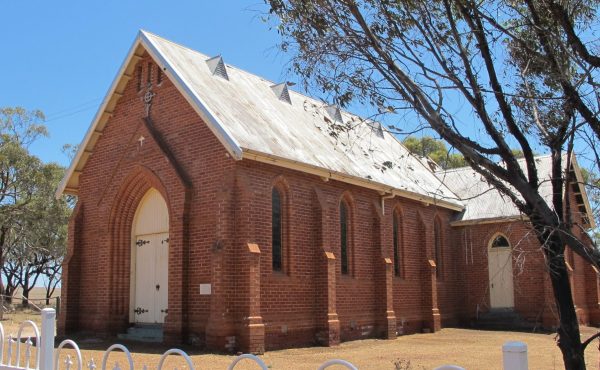

The church is set not far from the causeway, on higher ground to protect from floods. A line of four olive trees, believed to be over a hundred years old, lead from the small dirt carpark to its entrance. The building of the church dates to 1862 when it was consecrated by the first Anglican bishop of Perth.

The church building is constructed of local stone with some (relatively insignificant) later brick and concrete additions. But largely the church exists today as it has for the past 150 years, even as the settlement of Katrine has faded into obscurity.

But it is not only the church that interests me but also its surrounds, principally the forty some graves that form the small graveyard about it. Indeed, the church itself has no regular service other than on the Feast of All Souls (or the Sunday nearest) to commemorate those early pioneers who rest in its bounds.

St Saviour’s is, unremarkable for its vintage, a church surrounded by a graveyard. That is an arrangement that must have seemed natural to those who inhabited the town of Katrine but might seem nostalgic or romantic in the 21st century. Contemporary burials take place on a far larger (one is tempted to say industrial) scale than the forty graves about St Saviour’s.

Modern cemeteries are much more distinct spaces. They exist for burials and the visiting of graves and (usually) serve no other public function. They are thus very different from the arrangement at St Saviour’s where the dead are accommodated, as it were, in the centre of the township and as a part of a space devoted to public, weekly worship.

I wonder what lasting impression it might make on one mind to live where one has frequent (weekly, if not daily) impressions of the graves of one’s ancestors. Such a thought might seem to some to be a bit morbid, but I am not so sure that it might not have the opposite effect.

Doubtless there are pragmatic reasons why our practices of burial have change over time. Yet one effect of this, it seems to me, is the ostracization of death from everyday life wherein reminders or death and even public sorrow or mourning become embarrassing. Such attitudes can extend even to funerals which are sometimes rebranded as celebrations of life. One wonders where mourning or sorrow might be acceptable if not at a funeral.

How different is the practice, prevalent in many traditional cultures and recorded in the Bible, of hiring professional mourners who communicate a very public grief!

But sequestering death away from everyday life probably won’t make it seem less dreadful. And, if the rise of the modern cemetery in the 19th and 20th centuries was motivated by improving physical health, the case may be made that the 21st century must see the reintegration of death as a fact of everyday life for the improvement of our mental and spiritual health.

In any case, the graveyard at St Saviour’s is certainly shady and peaceful even (or especially) as it has been left behind by progress and development. In its corner rises a magnificent Lebanese cedar planted, it is believed, at a similar time to the olive trees. And beneath its branches lies the grave of Simon Viveash, who in 1862 donated the land to the church. May he, and all buried with him, rest in peace.