The following is a guest post by Mr. John Fitzgerald. The Dawson Society welcomes all contributions that work to promote the goals of the Society, principally intelligent engagement, open to spiritual realities, with cultural and philosophical ideas. Contributions, comments, complaints etc. can all be directed to mail@dawsonsociety.com.au

“Life only becomes real life when it receives its form from looking towards God.”

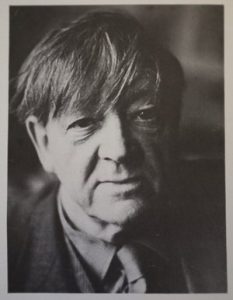

– Joseph Ratzinger, The Spirit of the LiturgyAmong the numerous writers and artists marked by Christopher Dawson’s thought – T.S. Eliot, G.K Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and more – the poet, painter, essayist, engraver, and calligrapher, David Jones (1895-1974) seems often overlooked. This is our loss, because Jones speaks directly to what the psychologist John Vervaeke calls the ‘meaning crisis’ currently impacting so much of contemporary politics, society and culture.

Jones was born and raised in London to a Welsh father and an English mother. He entered the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts at the age of 14 before serving as a private in the First World War, spending more time in the trenches (117 weeks) than any other British writer. On his return he resumed his studies, becoming by the end of the 1920s one of England’s leading painters and engravers. It was during this time that he became friends with Dawson. They shared an interest in Welsh history and legend, with Jones admiring the breadth of Dawson’s erudition, the scope of his historical vision, and his concise clarity of expression.

Jones began writing poetry in 1929 but suffered a severe nervous breakdown three years later. He was afflicted from that time on, sometimes to the point of incapacitation, by varying degrees of depression and mental instability. In Parenthesis, his epic war poem, was published in 1937, followed by The Anathemata in 1952, a multi-layered meditation on history and culture, structured around the form and shape of the Mass. In 1959, he published Epoch and Artist, a collection of essays on art and culture, exploring the thesis of ‘art as sacrament’ that informed his work. The Sleeping Lord, a compilation of shorter poems, rounded off his poetic oeuvre in the final year of his life.

Jones never married and remained poor always, living in a series of rented rooms in London. He had many loyal and devoted friends, however, who deeply appreciated his human and artistic qualities. Frequent visitors to his lodgings included W.H. Auden, Kathleen Raine, and Igor Stravinsky.

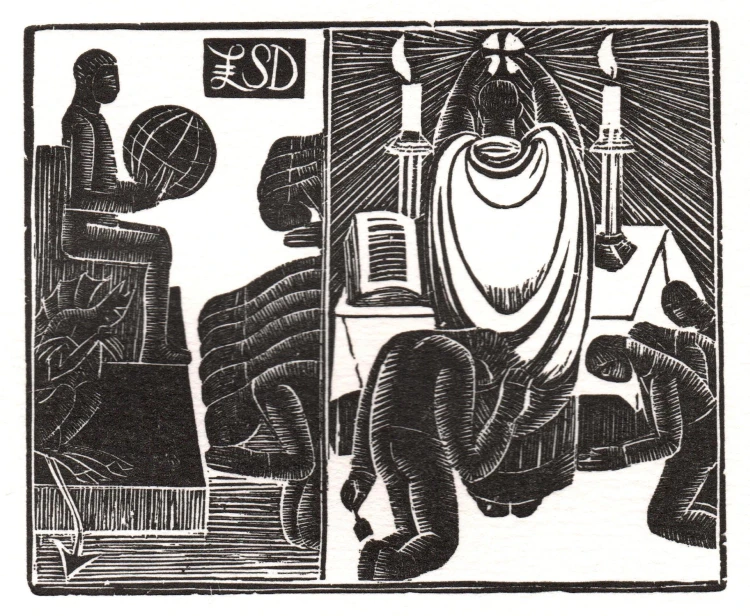

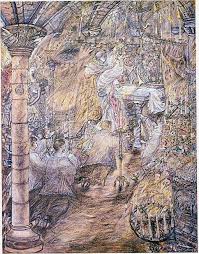

Jones was brought up as an Anglican and had never seen a Catholic Mass when in 1917 he saw by chance a military chaplain celebrating the Eucharist in a disused barn near Ypres. He was struck by the profundity of the rite, the reverence of the soldiers, and the overall air of depth and timelessness. This episode led directly to Jones’s conversion in 1921 and made a permanent impression on his life and art. He came to view the Mass as the crux and hinge-point of European civilisation, and we see this exalted understanding given fluent artistic expression in works such as Mammon and Worshippers and A Latere Dextro.

The artist’s vocation, Jones believed, is to participate in the ongoing redemption of the world. In this, the artist shares to an extent in the sacramental calling of the priest. In his essay Art and Sacrament Jones claims that art is an inherently sacramental activity – a non-utilitarian act that points beyond worldly contingencies to the unchanging truths of the Divine. Both art and sacrament, he concluded, are ‘signs’ directing us towards this higher reality, and he regarded this ‘sign-making’ as the human art par excellence, embedded into the fabric of our being. All pre-Christian religion, he argued, partakes in this sacramental outlook, foreshadowing the seven great sacraments given by God to the world through the Catholic Church. The Mass, therefore, stands at the apex of our long and winding history of sign-making. It ‘plugs one into the past,’ as Jones remarked. He held that it is only through becoming Catholic that post-Enlightenment man can establish meaningful contact with antiquity.

Jones saw himself as a pontifex, a builder of bridges between the enchanted, pre-modern worldview and the desacralised secularism of our era. But how does this apply in practice? Jones was a high modernist in style, so he was certainly not advocating a return to the customs and manners of earlier epochs. He would have concurred with Eliot’s assessment in Little Gidding that we cannot ‘follow an antique drum.’ It was modernity’s spiritual formlessness that troubled him, not its artistic content. He was under no illusions about how hard it has become today to perceive the hand of God at work in His creation. Materialism, rationalism, utilitarianism – all these bywords of the age – have colonised our minds and built a kind of Berlin Wall to keep us apart from the Real. In his late poem, A, a, a, Domine Deus, Jones gives voice to the modern seeker’s frustration in his or her insatiable longing for something more and other yet never being able (or allowed to) encounter it:

I have watched the wheels go round in case I might see the living creatures like the appearance of lamps, in case I might see the Living God projected from the Machine. I have said to the perfected steel, be my sister and for the glassy towers I thought I felt some beginnings of his creature, But A, a, a, Domine Deus, my hands found the glazed work unrefined and the terrible crystal a stage-paste … Eia, Domine Deus.

What Jones is striving after resides on a different level than a mere ‘return.’ It is the fire and spirit that animated Christian culture during and immediately after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Not only was the Faith preserved at this tumultuous time; it was brought forth in glory to baptise and redeem the nations of the new Europe. This is why the ancient hymn Vexilla Regis (Forward His Royal Banners Go) meant so much to him. First sung in 569 in Poitiers in honour of a relic of the True Cross, Jones saw it as a revelation of the combined strength of art and liturgy to regenerate a desolate spiritual and cultural landscape.

Dawson, of course, understood all this very well. ‘It is the Roman Church,’ he wrote in The Making of Europe (1932), ‘that is the centre of unity and guarantee of orthodox belief.’ Religion, for him, is the fount and wellspring that nourishes and gives life to a civilisation. Faith comes first. Everything else – politics, society, culture, etc.– flows downstream from that.

Our task, keeping this mind, is to fructify our epoch just as Venantius Fortunatus, the writer of Vexilla Regis, helped make his so richly fertile. Imagine, for instance, if everyone who stumbles on a Catholic Mass for the first time, as Jones did in 1917, felt the same power and vitality and had their lives similarly reconfigured. That might sound fantastical, but nothing is impossible to God, and we should set this as our benchmark and our norm. Imagine too if our literature, music and art – our sign-making activities – become charged and infused with the same transformative spirit? What restorative impact might this have on a world grown old and grey?

A ‘pole shift’ on this scale calls for an unshakeable faith in God and also in ourselves. It requires dedication, focus, and a realignment with the core root of our nature. What we will find at this genesis point is Homo Faber – man the maker – standing at an altar or before a blank canvas or an empty page, bringing something new into the world, for no other reason than that it is holy and beautiful to do so. An outward sign of inward grace.

As Jones reveals at the start of The Anathemata, this is where the civilisational wheels begin to turn again. This is where we renew our covenant with the Real:

We already and first of all discern him making this thing other. His groping syntax, if we attend, already shapes:

ADSCRIPTAM, RATAM, RATIONABILEM … and by pre-application and for them, under modes and patterns altogether theirs, the holy and venerable hands lift up an efficacious sign.